>>Readers Guide

When I was thirty years old, my novel The Great Santini was published, and there were many things in that book I was afraid to write or feared that no one would believe. But this year I turned sixty-five, the official starting date of old age and the beginning count down to my inevitable death. I’ve come to realize that I still carry the bruised freight of that childhood every day. I can’t run away, hide, or pretend it never happened. I wear it on my back like the carapace of a tortoise, except my shell burdens and does not protect. It weighs me down and fills me with dread.

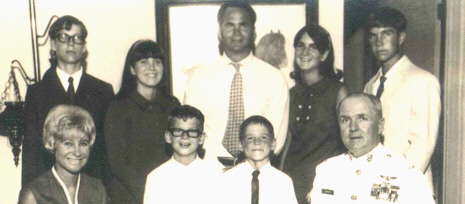

The Conroy children were all casualties of war, conscripts in a battle we didn’t sign up for on the bloodied envelope of our birth certificates. I grew up to become the family evangelist; Michael, the vessel of anxiety; Kathy, who missed her childhood by going to sleep at six every night; Jim, who is called the dark one; Tim, the sweetest one – and can barely stand to be around any of us; and Tom, our lost and never-to-be found brother. My personal tragedy lies with my sister, Carol Ann, the poet I grew up with and adored…

I’ve got to try and make sense of it one last time, a final circling of the block, a reckoning, another dive into the caves of the coral reef where the morays wait in ambush, one more night flight into the immortal darkness to study that house of pain one final time. Then I’ll be finished with you, Mom and Dad. I’ll leave you in peace and not bother you again. And I’ll pray that your stormy spirits find peace in the house of the Lord. But I must examine the wreckage one last time.

— From the memoir

Description

In this powerful and intimate memoir, the beloved bestselling author of The Prince of Tides and his father, the inspiration for The Great Santini, find some common ground at long last.

Pat Conroy’s father, Donald Patrick Conroy, was a towering figure in his son’s life. The Marine Corps fighter pilot was often brutal, cruel, and violent; as Pat says, “I hated my father long before I knew there was an English word for hate.” As the oldest of seven children dragged from military base to military base across the South, Pat bore witness to the toll his father took on his siblings, and especially on his mother, Peg. She was his lifeline to a better world, the world of books and culture, and despite the serial confrontations with his father Pat managed to claw his way towards a life he hardly could have imagined as a child.

Pat’s great success as a writer has always been intimately linked with his family life. While the publication of The Great Santini brought Pat much attention, the public rift it caused with his father generated more attention still. Their long-simmering conflict burst into the open, fracturing an already battered family even further. But as Pat tenderly chronicles here, even the oldest of wounds can heal. In the final years of his life, Don Conroy and his son reached a rapprochement of sorts. Quite unexpectedly, the Santini who had freely doled out backhanded slaps targeted his ire on those who had turned on Pat over the years. He defended his son’s honor.

THE DEATH OF SANTINI is a heart-wrenching account of personal and family struggle, and a poignant lesson in how ties of blood can both strangle and offer succor. It is an act of reckoning, an exorcism of demons, but one whose ultimate conclusion is that love can soften even the meanest of men, giving meaning to one of the most often quoted lines from his bestselling novel. The Prince of Tides: “In families there are no crimes that cannot be forgiven.”

The memoir is dedicated to Pat’s siblings. Here this is in Pat’s words:

This book is dedicated with love and gratitude to my brothers and sisters”:

Carol Ann, the Conroy family poet and fabulist, the great explainer to it all;

Mike, the keystone, the calm in the midst of the family storm, the center that always holds;

Kathy, the family nurse, Santini’s caretaker and confessor, the azalea crafted with iron;

Jim, our brightest, most brilliant sibling, also our dark and hilarious commentator on the flawed clan;

Tim, the kindest and sweetest Conroy, a compassionate worker with special needs kids who brought joy into the lives of all he taught;

Tom, our lost boy and baby brother whose suicide was the mortal wound to the heart of the family and reminded us how bad it really was.

Praise

“An emotionally difficult journey that should lend fans of Conroy’s fiction an insightful back story to his richly imagined characters. One of the most widely read authors from the American South puts his demons to bed at long last. One doesn’t have to have read The Great Santini to know that Pat Conroy was deeply scarred by his childhood. It is the theme of his work and his life, from the love-hate relationship in The Lords of Discipline to broken Tom Wingo in The Prince of Tides to the mourning survivor Jack McCall in Beach Music. In this memoir, Conroy unflinchingly reveals that his father, fighter pilot Donald Conroy, was actually much worse than the abusive Meechum in his novel. Telling the truth also forces the author to confront a number of difficult realizations about himself. “I was born with a delusion in my soul that I’ve fought a rearguard battle with my entire life,” he writes. “Though I’m very much my mother’s boy, it has pained me to admit the blood of Santini rushes hard and fast in my bloodstream. My mother gave me a poet’s sensibility; my father’s DNA assured me that I was always ready for a fight, and that I could ride into any fray as a field-tested lord of battle.” Conroy lovingly describes his mother, whom he admits he idealized in The Great Santini and corrects for this book. Although his father’s fearsome persona never really changed, Conroy learned to forgive and even sympathize with his father, who would attend book signings with his son and good-naturedly satirize his own terrifying image. Less droll is the story of Conroy’s younger brother, Tom, who flung himself off a building in a suicidal fit of schizophrenia, and Conroy’s combative relationship with his sister, the poet Carol Conroy. The moving true story of an unforgiveable father and his unlikely redemption.”

Kirkus Starred Review

“…Conroy has fashioned a memoir that is vital, large-hearted and often raucously funny. The result is an act of hard-won forgiveness, a deeply considered meditation on the impossibly complex nature of families and a valuable contribution to the literature of fathers and sons…”

The Washington Post

“Conroy remains a brilliant storyteller, a master of sarcasm, and a hallucinatory stylist whose obsession with the impress of the past on the present binds him to Southern literary tradition…”

The Boston Globe

Praise for Pat Conroy

“Conroy is a master of language.”

The Atlanta Journal

“Conroy is an immensely gifted stylist….No one can describe a tide or a sunset with his lyricism and exactitude.”

Chris Bohjalian, The Washington Post

“Conroy writes with a momentum that’s impossible to resist.”

People

“Conroy takes aim at our darkest emotions, lets the arrow fly and hits a bull’s-eye almost every time.”

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Pat Conroy’s writing contains a virtue now rare in most contemporary fiction: passion.”

The Denver Post

“Few novelists write as well, and none as beautifully.”

Lexington Herald-Leader

“God preserve Pat Conroy.”

The Boston Globe

“Conroy announces that the fictions he has spun over his long, celebrated literary career aren’t really fictions. They’re diamonds hauled up to earth and into the light of day from the dark and bottomless mine of his Southern clan. Conroy tends to paint in extravagant strokes and SANTINNI instantly reminded me of the decadent pleasures of his language, of his promiscuous gift for metaphor and of his ability, in the finest passages of his fiction, to make the love, hurt or terror a protagonist feels seem to be the only emotion the world could possibly have room for, the rightful center of the trembling universe.”

New York Times Book Review